A Charter Day Sermon

The Rev. Dr. Stephanie May

September 10, 2023

First Church in Boston

We are here today celebrating Charter Day because on September 7, 1630, Puritan leaders of the Massachusetts Bay Company recorded their decision that “Trimountaine shall be called Boston,” thereby giving the land the English name by which it is still known. First Church Boston dates its own beginning to just weeks earlier when the settlers signed a covenant on July 30th to form a congregation. The values expounded in this first covenant convey a laudable vision of “mutual love” and “respect each to other.” And yet, there in the first line “We whose names are hereunder written…” also lie the seeds of enslavement. For with this line, the covenant committed those promises of love and respect to the “we” of those signed, but not necessarily to the “stranger” outside the bonds of covenant. Within the decade, this delineation of belonging helped to justify the practices of enslaving Indigenous, African, and Caribbean people by Puritan colonists. So also today, defining who belongs within our “we” as a church, a city, a nation remains an ongoing question.

Artist Bethany Collins explores this question of belonging in America through her 2017 book, “America: A Hymnal.” In her volume, she compiles 100 versions of the song “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.” Showcasing lyrics that have been written and rewritten to support a range of causes—including both abolition and the Confederacy—each version lays claim to different visions of who belongs and who is free.

The “Hymnal” is currently displayed at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem at the front of a small white room, with four wooden benches before it. Within this simple chapel, a recording plays of six singers performing all 100 versions of “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” simultaneously. The layered music creates a feeling of “familiar dissonance” as tunes and texts crisscross during the work’s 3 hours and 25 minutes. The patriotic longing conveyed in one voice and version becomes overtaken by the rising sound of another voice and version. Immersed in multiplicity, no one voice defines the song or the story of the song.

Questions of belonging also emerge in a current exhibit on the National Mall in Washington D.C., “Pulling Together,”which asks—“what stories remain untold on the National Mall?” Amidst the permanent works of stone, these temporary installations explore which monuments are missing in the memorializing our national story? For example, a massive thumbprint made of glass by Wendy Red Star, who is Apsáalooke (Crow), remembers the many treaties ratified by Indigenous leaders using their thumbprint or an X, rather than their signature. Placed next to the 56 signers of the Declaration of Independence Memorial, the contrast of the two memorials and kinds of signatures asks us to consider which story we tell? The story of white European men claiming freedoms for themselves or the story of Indigenous leaders ceding their land in tears and violence? Or both?

Down the Mall, on the plaza in front of the Lincoln Memorial, a joyful sculpture of Marian Anderson by artist vanessa german rises from the concrete to commemorate Anderson’s 1939 performance at the site. As you may know, Anderson enjoyed international fame as an opera singer in the early 20th century. Yet, because she was African American, the Daughters of the American Revolution denied her access to perform at their large hall. Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt then helped to arrange for the Department of the Interior to approve a concert on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. Before a multi-racial crowd of 75,000 on Easter Sunday, Anderson began by singing “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.” Notably, she altered the first verse “of thee I sing” into the phrase “to thee we sing.” In a 2014 article on Anderson, NPR reported:

A quiet, humble person, Anderson often used “we” when speaking about herself. Years after the concert, she explained why: “We cannot live alone,” she said. “And the thing that made this moment possible for you and for me, has been brought about by many people whom we will never know.”

Who is the “we” in the stories we tell of America?

Challenged to confront hidden stories, a number of historical institutions have been reckoning with the legacy of slavery in America in recent years. For example, in 2022, the Committee on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery issued a report which includes a discussion of John Winthrop and the beginning of slavery in Boston. In 1636, the year Harvard was founded, the Pequot War was underway with many captured Pequot becoming enslaved. Winthrop himself enslaved the wife of a Pequot sachem and her two children. Winthrop also instructed the newly built ship Desire to carry 17 Pequot War prisoners to Bermuda. According to the Harvard Report, “Two years later, on February 26, 1638, the Desire returned to Boston Harbor carrying cotton, tobacco, salt, and an unspecified number of enslaved Africans who had been purchased on Providence Island.”[1]

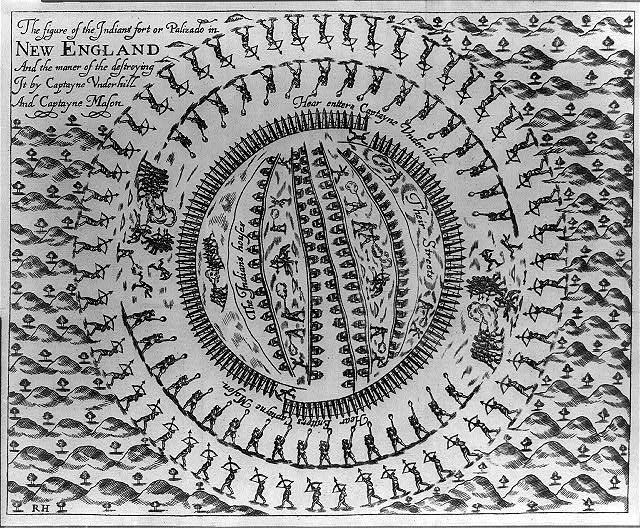

Perhaps like me, your knowledge of the Pequot War is rather thin. However, as I began to study the history of enslavement in New England for today’s service, I quickly realized the importance of the Pequot War to this history. As Margaret Newell’s 2015 book, Brethren by Nature, makes clear, “New England Indians formed a significant part of New England’s slave population.”[2] To better understand the War, I visited the Pequot Museum at the Mashantucket Pequot Reservation north of Mystic, Connecticut. There I learned how English soldiers burned the Pequot village at Mystic, trapping and killing hundreds of adults and children. Then, in a stunning act of cultural genocide, any remaining Pequot were forbidden by the conquering English to call themselves by the name Pequot or to inhabit their ancestral lands.

And yet, by framing the Pequots as aggressive outsiders, the Puritan leaders defined the conflict as a “just war,” drawing on established doctrine that enabled enslaving captives in a defensive conflict.[3] (I’ll add that the origins of the War make the argument of a “defensive conflict” murky at best.) Several years later, the 1641 Massachusetts Bay Colony’s “Body of Liberties” further encoded the legality of enslaving captives and the trafficking of enslaved persons. Specifically, the code barred enslavement “unless it be [for] lawfull captives, taken in just warrs, and such strangers as willingly sell themselves, or are solde to us.”[4] Historian of New England slavery Jared Ross Hardesty explains the significance of the word “strangers” in this passage:

“Likewise, the reference to ‘strangers’ sold to the colonists was coded language for African slaves. Within a decade after the settlement of New England, then, chattel slavery was not only legal but also racialized, a status reserved solely for Indians and Africans.”[5]

Thus, just eleven years after the Puritans arrival in Boston, enslaved Indians and Africans were legally excluded from the “we” of English liberties and freedoms.

In these limited minutes here this morning, I cannot adequately convey the full history of enslavement in New England. I am grateful to the Partnership of Historic Bostons for offering a series of lectures throughout this fall which provide an opportunity to learn much more. Before I end, I want to share a story which awakened me to the presence of slavery in New England.

About 17 years ago, I began to plan a trip to Newport, Rhode Island. In perusing websites, I read that the second-floor rooms of the Breakers Mansion had been designed by Ogden Codman. Turning to my partner, Bill, a Codman descendent, I asked if he was related? From this casual exchange, I began to explore the Codman family history. As I researched, I learned that in 1755, John Codman, a merchant and enslaver, was poisoned by his slaves, Mark, Phillis, and Phoebe. Remarkably, you can read the entire story and court transcript online. The story of Mark, Phillis, and Phoebe is a story of resistance to being separated from family members and of a hope for change. In short, they conspired to acquire arsenic and then administered the poison in food and drink to Codman. Found out and convicted of petit treason, Phoebe was sold out of the colony for her lesser role, while Phillis and Mark were both executed—Phillis burned at the stake and Mark hung nearby. Following Mark’s death, his body was placed in a gibbet, a metal cage, and hung at Charleston Neck.

Twenty years later, on Paul Revere’s famous ride to warn the countryside that the British were coming, Revere passed by where Mark hung. We know this because in 1798 Revere wrote an account of his ride to Jeremy Belknap, the corresponding secretary of the Massachusetts Historical Society.[6] In his letter, Revere wrote, “After I had passed Charlestown Neck, & got nearly opposite where Mark was hung in chains, I saw two men on Horseback, under a Tree.” In 1798, Revere could still confidently reference the location of where Mark had been placed 44 years previously. While it is not clear whether Mark remained hanging there in 1798, Revere’s letter suggests that Mark was still there in 1775. 20 years after his death Mark’s body had quite literally become a landmark.

How then does the story of Mark, Phillis, and Phoebe, which was so well known for decades in the late 18th century, become widely unknown today? And yet, at the same time, many of us do know the version of Revere’s story recounted by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. “Listen my children and you shall hear, of the midnight ride of Paul Revere”—a sanitized version of the ride in which slavery appears nowhere. Indeed, an Atlantic editorial note indicates that Longfellow, an abolitionist, published the political poem in January 1861 to rally the nation to its founding principles after South Carolina became the first state to secede from the Union in December 1860. Rather than reveal the presence of slavery in New England, Revere’s ride becomes a tool for the abolitionist North to patriotically defend the Union against Southern enslavers.

For me, this story of Revere’s ride conveys the erasure not only of Mark’s brutalized body but also of the presence of slavery in Boston and New England. Whose stories are we telling? Whose stories have become lost or hidden? Whose stories do we remember with monuments in public squares, the National Mall, or at the front entrance to First Church Boston?

In the poem “Let America Be America Again,” Langston Hughes makes evident the tension of who is and is not included in the story of America: “(America never was America to me.)” He also underscores that not everyone had their freedom in America: “(There’s never been equality for me, Nor freedom in this “homeland of the free.”). And while Hughes does not stop short in laying out his critique of America’s exclusions and inequalities, he also holds up the possibility that the promises of America may yet be!

The land that never has been yet—

And yet must be—the land where every man is free.

The land that’s mine—the poor man’s, Indian’s, Negro’s, ME—

Who made America,

Whose sweat and blood, whose faith and pain,

Whose hand at the foundry, whose plow in the rain,

Must bring back our mighty dream again.

On this day of marking beginnings, perhaps we might commit ourselves both to a new chapter that does not shrink from the full truth of enslavement in New England nor from the work of ensuring an ever more inclusive “we” in the stories we tell and the communities we build.

This call to a more inclusive “we” literally rings out in Paul Ramírez Jonas’ contribution to the “Beyond Granite” exhibit on the Mall—a massive metal structure of suspended bells which play the tune “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” except for the final note. Passerby are invited to play this final note on a 600-lb bell as they proclaim for what or whom they ring this bell of freedom. When I first approached the structure, a young, white man staffing the exhibit was helping a middle-aged, brown-skinned woman in a sari prepare to ring the final note. As I listened to the song and watched her ring the final note, I wondered for who or what she rang. I wondered how many notes, how many more people and stories are yet to be proclaimed as fully belonging here in America.

As we laud the Puritans’ founding values of freedom, mutual love, and respect, may our own embodiment of these values leave space for an ever more inclusive “we” of wider belonging. And may that wider belonging include the stories of enslavement and resistance of Indians, Africans, and Caribbean people whom we may never fully know, but whose lives resound still in the institutions, culture, and world we inhabit today.

So may it be. Amen.

[1] The Presidential Committee on the Legacy of Slavery, The Legacy of Slavery at Harvard: Report and Recommendations of the Presidential Committee, https://legacyofslavery.harvard.edu/ report and (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2022), 13. As support, the Report cites Mark Peterson, The City-State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of An Atlantic Power, 1630–1865 (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019), 19.

[2] Margaret Ellen Newell, Brethren by Nature: New England Indians, Colonists, and the Origins of American Slavery (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), 3.

[3] Brethren by Nature, 10.

[4] Legacy of Slavery at Harvard, 13.

[5] Jared Hardesty, Black Lives, Native Lands, White Worlds: A History of Slavery in New England, (Amehurst and Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2019), 14.

[6] Notably Jeremy Belknap (1744-1798) would have been relatively young at the time of Codman’s murder. Nonetheless Revere assumed his awareness of the story and Mark’s location.